‘Reef Safe’ Sun Protection: an update

We have previously written about the damaging effects of sunscreen on coral reefs and have banned the use of commercial non ‘reef safe’ sunscreens at Reef Doctor. In this new blog, Reef Doctor volunteer Elizabeth Pasea updates us on the issue and recommends the best approach for protecting your skin from the harmful effects of UV radiation with minimal impact to coral reefs:

“Growing up under a hole in the ozone layer in New Zealand, I was aware of how important sunscreen is to protect against skin cancer. I have more recently learned that the ingredients in most commercial sunscreens are damaging to coral. Awareness is spreading; Hawaii has recently banned the ingredients octinoxate and oxybenzone due to their negative impact on coral ecosystems.

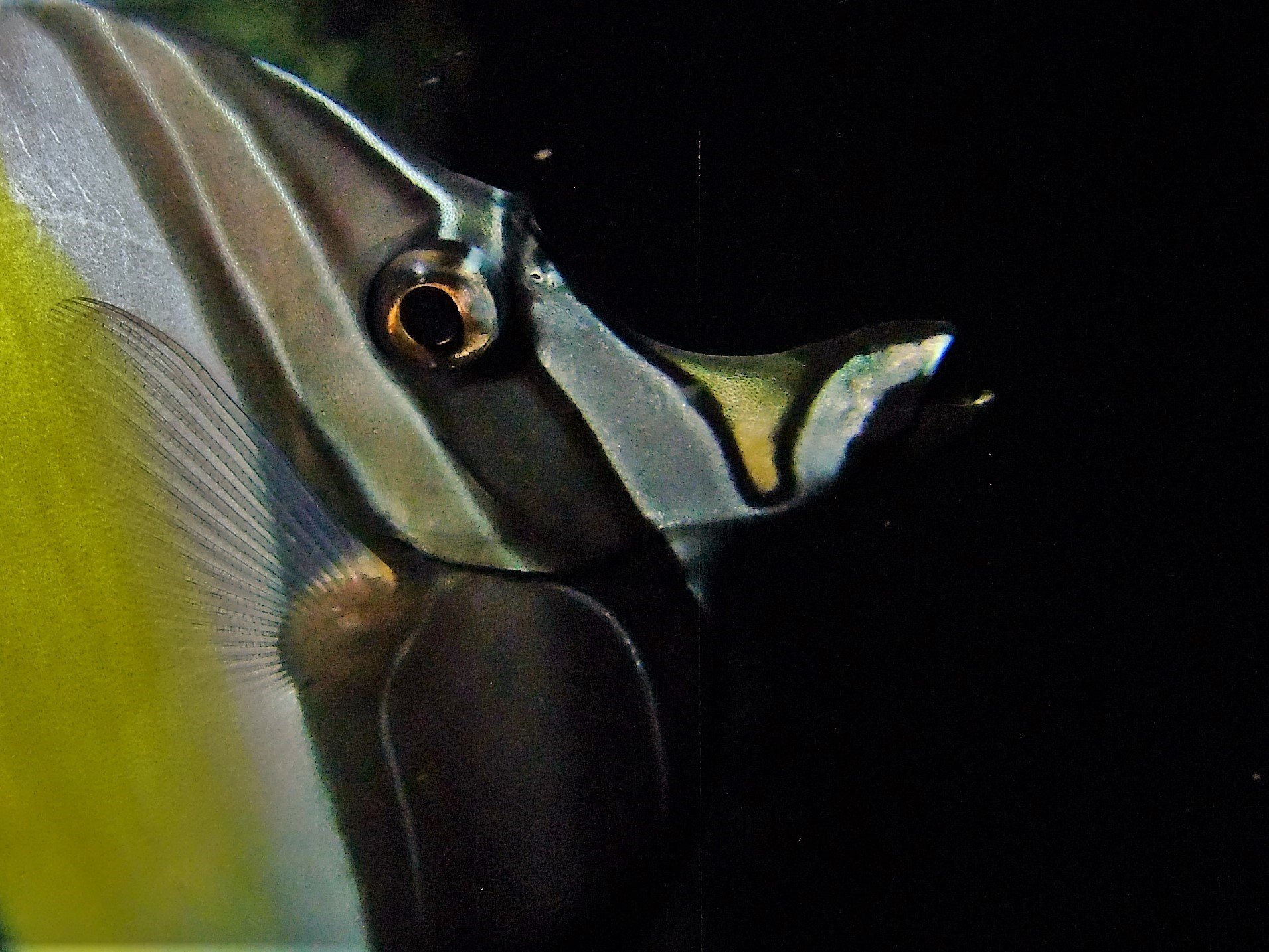

Studies have shown that even ingredients advertised as ‘reef safe’ can still increase oxidation and acidity levels in water and contribute to coral stress, where they may expel the algae which reside in them and give the coral it’s colour; the process known as coral bleaching. Non-organic sunscreen ingredients, zinc oxide or titanium dioxide, are less toxic than petroleum-based ingredients; however their nano particles may still damage coral.

80% of the ReefDoctor volunteers currently on camp have titanium dioxide based sunscreen, and 20% zinc oxide. Most of us found that we had to search hard for these products – they were not the most readily available products.

One of the things to notice when arriving in this part of Madagascar is that some of the women wear mud on their faces during the day for sun protection, as demonstrated in the photo below by Reef Doctor Support staff member Hortence. As it happens, titanium dioxide is just about to start being mined in Ranobe, not far from the Reef Doctor camp, science is catching up with local Vezo custom!

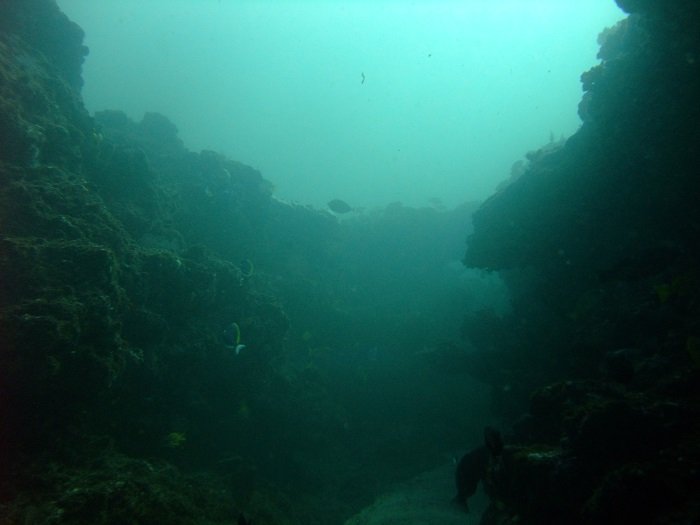

When diving at Reef Doctor, whether gathering data on the health of the reef or transplanting coral, we try to minimise our application of ‘reef-safe’ sunscreen to dry skin; when applied to wet skin it is liable to rinse off straight away. We also prefer hats and clothes to protect our skin when on the boat and during surface intervals.

It’s not only swimmers and divers who introduce sunscreen and other chemicals to the coral environment: chemicals used on land and washed off into many municipal waste systems also end up in the ocean. A recent study (Corinaldesi et al, 2018) showed that patented titanium based ingredients ‘Optisol’ And ‘Eusolex T2000’ have significantly lower levels of toxicity to coral than zinc oxide. Hopefully, we will see more products with these ingredients available to buy soon.

In the meantime, please read the ingredients! The conservative application of products containing non-nano zinc oxide and titanium oxide applied to dry skin remains the best option to help ensure coral ecosystems survive beyond 2050.”

Blog by Elizabeth Pasea

Photo credits: Elizabeth Pasea & Margot Chapon