Madagascar is Burning

In this article, Reef Doctor Honko Manager Antoine Lechevalier discusses the issues of drought, fire and charcoal production that are plaguing the Atsimo-Andrefana (southwest) region of Madagascar.

“These days Madagascar is on fire. When taking the RN7 from Antananarivo to Toliara, hundreds of fires burning in the savanna that replaced the original forest can be seen.

The situation on the coast is not better. On the 10th of March 2018, 8.5 Ha of mangrove and 14 Ha of saltwater marsh including reeds, grasses, and shrubs (rushes) of Belalanda, in SW Madagascar, were destroyed by fire. This event highlights the fire problem in Madagascar. Despite anti-fire precautions and awareness programmes, people are pushed by poverty, having little or no alternative livelihood strategies, continue burning the forest and producing charcoal for their survival.

The island nation of Madagascar is famous for its endemic biodiversity. Since it split from the African continent an estimated 160 million years ago, it has developed its own distinct ecosystems and extraordinary wildlife. An approximate of 89% of its plant life 95% of its reptiles, and 92% of its mammals exist nowhere else on Earth. Madagascar’s more than 4,800 km of coastline and over 250 islands are home to some of the world’s largest coral reef systems and most the extensive mangrove areas in the Western Indian Ocean.

The small-scale but widespread clearances of the forests have already had a profound effect on the island. 90% of Madagascar’s original forests have been lost due to human activity since their arrival a mere 2000 years ago. Aerial photographs and remote sensing images indicate that almost 40% of Madagascar’s forest cover disappeared from the 1950s to 2000 (Harper et al. 2007). It is no wonder then, that most of Madagascar’s unique and endemic flora and fauna face extinction. Annually enormous forest areas of Madagascar are threatened by flames, from uncontrolled wildfires and lands burned for grazing. This problem concerns the entire island. Lush rainforests, tropical dry forest, grassland and even mangrove are impacted. Each year, an estimate of half of the island’s grasslands and woodlands burn. It is the results of three activities; slash and burn agriculture, logging for timber and charcoal production. These practices are jeopardising the island’s habitats. As a result, several charismatic species such as many species of lemurs and chameleons that evolved here over millions of years may become extinct before the end of the century.

One of the reasons for this extensive deforestation is that Madagascar is amongst the world’s poorest countries and people’s day-to-day income generation is focused on the exploitation of natural resources. Rural populations of which over 70% have less than 4 years of education live off the land developing ways to exploit an already stressed ecosystem (STRAT 2018). Deforestation has long been an issue for Madagascar and, to support the population increase of 4.6% per year (STRAT 2018) people must seek new land to cultivate, notably in the forests.

The Atsimo Andrefana region is located in South-West Madagascar. It is the biggest and, with a population density of 31 inhab/km², one of the least densely populated regions of Madagascar. The region is struck by long-term drought. Since May 2015, there has been 50% less rain than normal levels. The lack of rain impoverishes crops and seeds stocks, leading to poorer harvests and increasing poverty and malnutrition. According to the Plan de réponse stratégique à la sécheresse dans le grand-sud (Strategic response plan for the drought in the south), 49% of the population suffers from alarming hunger level in the Ampanihy district and thousands of people are malnourished. Hoping to find work, people move to the mines or the cities. The coastal areas are also refugee for poverty-stricken communities that increase pressure on the fish resources and threaten the remaining mangrove forests located in the north. Furthermore, droughts have forced hundreds of farmers into charcoal production. The lack of control makes it an easy but unsustainable source of income. Consequently, the endemic spiny forests are being destroyed at an alarming rate.

In 17 years, the Atsimo Andrefana region has lost 60% of its intact forests and 66% of its degraded forests. While drought forces people to look for alternative livelihoods, commercial interests in charcoal increases. Considering the fact that a bag of charcoal is worth much more in the highlands than on the coast, illegal charcoal exportation is often a tempting source of incomes for the rural, poverty-stroked, population of the South-West. The number of charcoal producers increases every year and so does the uncontrolled wildfires initiating from charcoal farms.

The fire that destroyed 8.5 Ha of the mangrove of Belalanda may not be intentional but it is likely that it started from a site that produces charcoal and then spread to the reeds and forest. It shows how the mangroves and forests of Atsimo Andrefana are vulnerable to fires. Especially with drought increasing human pressure and making the forest more prone to catching fire.

Forests, and especially mangroves, are extremely valuable. They reduce atmospheric carbon concentrations, provide shelter for Madagascar’s unique biodiversity and help to produce rain. These environments are even more valuable in a country threatened by desertification and lack of resources.

In light of these increasing problems, it appears that policy, strategy and clear regulation need to be developed and implemented to stop the fires that destroy Madagascar. Organisations such as Reef Doctor are working really hard in the field to tackle these massive problems. Mangrove cover at the Reef Doctor Honko (mangrove) project site is increasing thanks to replanting efforts and community-led management initiatives, and a dynamic agroforestry project aimed to improving livelihoods and restoring natural forest has recently started. However encouraging the results may be, it is more than necessary for national authorities to take a strong hold on the issues.

Farmers need to be trained in new ways to produce drought-resistant crops and use the same plot of land instead of cutting forests down to cultivate new fields (tavy or slash and burn agriculture). The local community needs to better control and manage local natural resources. Forests should be planted and managed in a sustainable way in order to be used as sources of charcoal in the mid and long terms.

Written by Antoine Lechevalier

Article originally featured on the blog site https://protectmadagascar.wordpress.com created by Sasa Danon

Since 2001 the 19th of November has been World Toilet Day. Not the most glamorous of days, admittedly but one that is an essential reminder that billions of people worldwide suffer disease, indignity and exposure to threat daily because of the lack of access to safe clean water, sanitation infrastructure and proper hygiene practices (WASH). Around the world, 2.4 billion people lack access to improved sanitation (a connection to a sewer, septic tank, ventilated pit latrine or some simple latrines –ref WHO/UNICEF. Meeting the MDG WHO: Geneva, 2004) and one third of the global population has no access to any kind of toilet at all.

Since 2001 the 19th of November has been World Toilet Day. Not the most glamorous of days, admittedly but one that is an essential reminder that billions of people worldwide suffer disease, indignity and exposure to threat daily because of the lack of access to safe clean water, sanitation infrastructure and proper hygiene practices (WASH). Around the world, 2.4 billion people lack access to improved sanitation (a connection to a sewer, septic tank, ventilated pit latrine or some simple latrines –ref WHO/UNICEF. Meeting the MDG WHO: Geneva, 2004) and one third of the global population has no access to any kind of toilet at all.

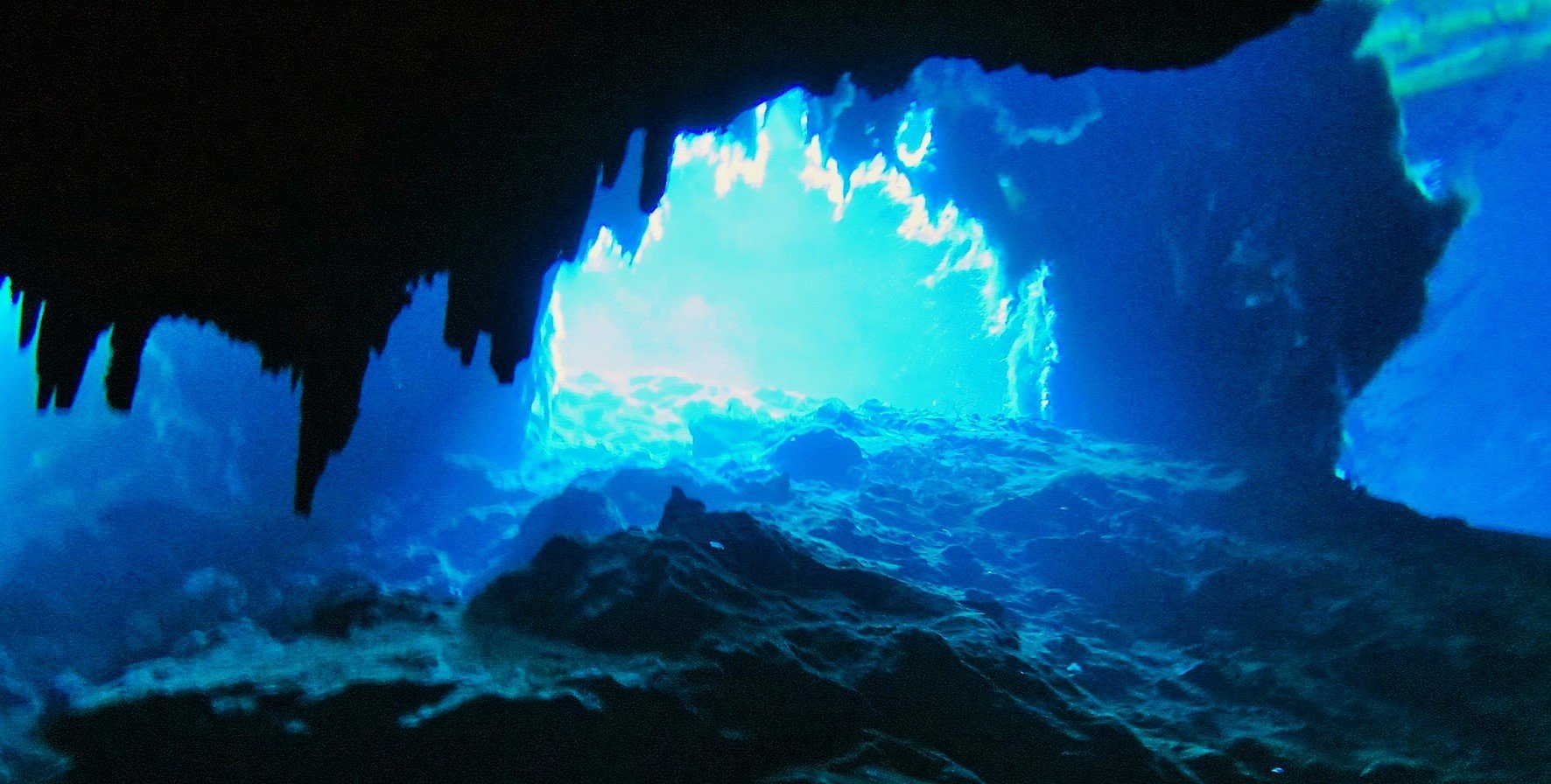

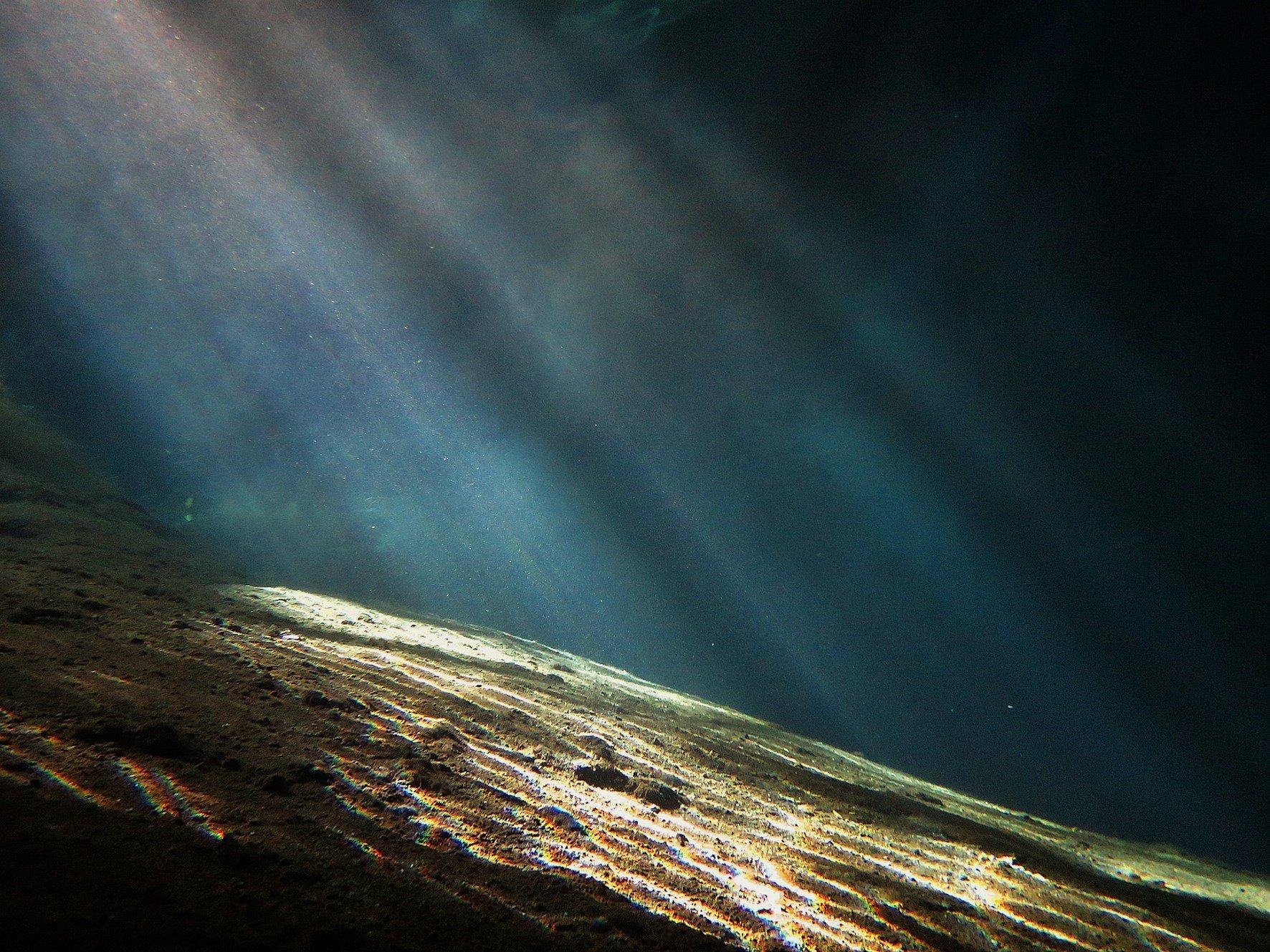

ve system and MCDA was born. The association gets to explore amazing sites and carry out very technical, often dangerous dives. They also get called on when anyone wants to access the system. On this occasion MCDA was contacted by a Japanese documentary film crew who needed some footage of water flow in the cavern at the entrance to the cave system and some divers to film it, and Andre and I got to help out with filming. Both of us had dived in caverns before but that didn’t make the prospect of this dive any less exciting as we were diving a cavern that very few other people have seen, and with one of the people who discovered and explored it for the first time.

ve system and MCDA was born. The association gets to explore amazing sites and carry out very technical, often dangerous dives. They also get called on when anyone wants to access the system. On this occasion MCDA was contacted by a Japanese documentary film crew who needed some footage of water flow in the cavern at the entrance to the cave system and some divers to film it, and Andre and I got to help out with filming. Both of us had dived in caverns before but that didn’t make the prospect of this dive any less exciting as we were diving a cavern that very few other people have seen, and with one of the people who discovered and explored it for the first time. which stretch from the edge 10 meters down and into the water. Tanks and gear were lowered down and we started kitting up on the small mound in the middle of the sinkhole. We lowered ourselves slowly into the water so as to disturb the silt as little as possible and finned our way into a beautiful scene that was out of this world.

which stretch from the edge 10 meters down and into the water. Tanks and gear were lowered down and we started kitting up on the small mound in the middle of the sinkhole. We lowered ourselves slowly into the water so as to disturb the silt as little as possible and finned our way into a beautiful scene that was out of this world. without sight, looked at fossils of lemurs and crocodiles, and explored as much of the cavern as we had time to. I could have stared at the trees through the water for days and spent ages admiring the beautiful rainbow reflections made by the sun on the silt. We couldn’t enter the cave properly as neither of us is a certified cave diver but diving the cavern was spectacular and there was so much to see that once we had finished the filming we were very happy to keep swimming until we had used up all our air. My request for five more minutes at the end of the second dive turned into 11 minutes and I still left reluctantly. I’ve been lucky enough to do some really amazing dives and this one is definitely in my top 10. I don’t think I’m going to become a world famous videographer or lighting technician anytime soon but this dive and experience will stay with me for the rest of my days. And I think it will take a long time to shake the desire to get cave certified.

without sight, looked at fossils of lemurs and crocodiles, and explored as much of the cavern as we had time to. I could have stared at the trees through the water for days and spent ages admiring the beautiful rainbow reflections made by the sun on the silt. We couldn’t enter the cave properly as neither of us is a certified cave diver but diving the cavern was spectacular and there was so much to see that once we had finished the filming we were very happy to keep swimming until we had used up all our air. My request for five more minutes at the end of the second dive turned into 11 minutes and I still left reluctantly. I’ve been lucky enough to do some really amazing dives and this one is definitely in my top 10. I don’t think I’m going to become a world famous videographer or lighting technician anytime soon but this dive and experience will stay with me for the rest of my days. And I think it will take a long time to shake the desire to get cave certified.

er). However, I was given some refillable non-lethal lighters recently by a volunteer who was going back to Europe so I decided to get them filled.

er). However, I was given some refillable non-lethal lighters recently by a volunteer who was going back to Europe so I decided to get them filled.

At Reef Doctor, we reuse and re-purpose as much as possible from collecting empty water bottles to make floats for the seaweed farms to composting food waste. Empty jars become powdered milk containers and no one ever throws away a plastic bag (on 1st October 2015 it became illegal for shops in Madagascar to give away plastic bags). Almost everyone on camp has a plastic bag in their back pack to store street food bought in the village so as not to use up the vendors paper cones made for holding food (they have to buy exercise books or use their children’s homework!). A group of the interns and staff are currently working on a project to re-purpose an old solar oven into a dome structure to grow coral on for our latest coral gardening project – more about that at a later date.

At Reef Doctor, we reuse and re-purpose as much as possible from collecting empty water bottles to make floats for the seaweed farms to composting food waste. Empty jars become powdered milk containers and no one ever throws away a plastic bag (on 1st October 2015 it became illegal for shops in Madagascar to give away plastic bags). Almost everyone on camp has a plastic bag in their back pack to store street food bought in the village so as not to use up the vendors paper cones made for holding food (they have to buy exercise books or use their children’s homework!). A group of the interns and staff are currently working on a project to re-purpose an old solar oven into a dome structure to grow coral on for our latest coral gardening project – more about that at a later date.