Reef Doctor Project Update

Over the past 4 years, our efforts have been focused on the development of a comprehensive community-driven plan that spans 55 villages, with five representatives per village from four key communes in the provincial region of Atsimo-Andrefana, Toliara, SW Madagascar: Belalanda, Maromiandra, Manombo, and Ankilimalinika.

This approach involves community representatives directly in conservation and sustainable management practices, fostering local leadership while ensuring that solutions are contextually relevant and sustainable for the communities themselves.

Our work is now centred on three primary pillars:

Food Security: Our objective is to establish a reliable and sustainable food supply that can withstand environmental challenges and changing seasons. We work with communities to develop sustainable food sources, such as fisheries and agriculture, that can provide long-term nutritional stability. By creating accessible and sustainable food resources, we improve health outcomes, reduce dependency on external aid, and empower communities to manage their own food supplies effectively.

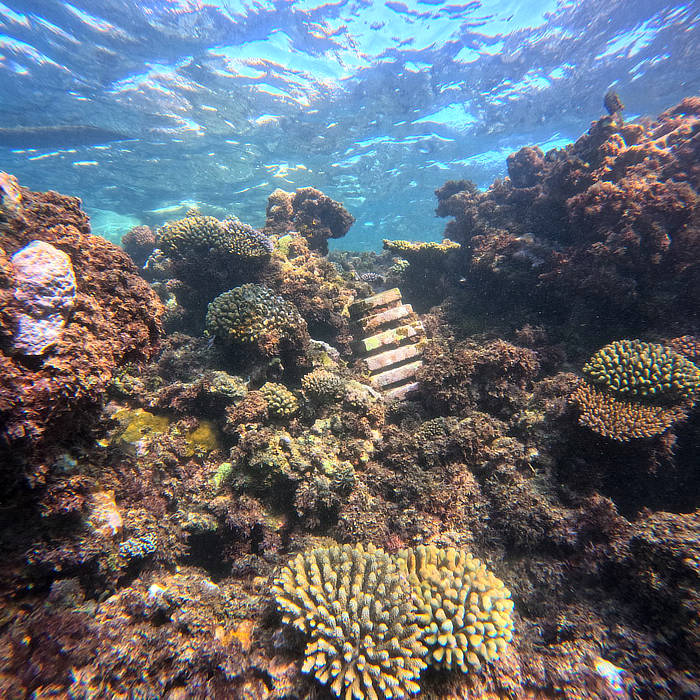

Conservation: Environmental sustainability is at the core of our approach. We work closely with local leaders and community members to implement conservation practices that protect local ecosystems, especially coastal and marine areas. Our conservation strategies include building artificial reefs and restoring degraded areas to promote biodiversity, which in turn supports the ecosystem services that local communities rely on, like fisheries. This pillar ensures that the natural resources remain healthy and accessible for future generations while providing immediate ecological and economic benefits.

Social Security: We aim to create a secure social environment within these communities by building trust, resilience, and mutual support. Through Social-Emotional Learning (SEL) and Mental Health and Psychosocial Support (MHPSS), we equip community members with the skills needed to address conflicts peacefully, build emotional resilience, and provide mutual support. Recognizing the importance of addressing gender-based violence (GBV), we incorporate GBV awareness and prevention into our programs, empowering individuals to recognize, respond to, and reduce instances of violence. By fostering these skills and support systems, we can create an environment that reduces social tensions, enhances safety, and promotes cohesive, respectful relationships within and between villages.

Our overarching objective is to empower these communities through active participation in all three pillars, building a foundation of social and economic resilience that aligns with sustainable environmental stewardship. Through this model, we aim to create a self-sustaining cycle of empowerment, stability, and conservation that can be adapted and maintained by the communities themselves long after direct support concludes.

ARMSRestore Project

In collaboration with the ARMSRestore consortium, we are currently conducting an ambitious initiative within the Bay of Ranobe MPA, involving the construction of 6 hectares of artificial reefs. This project employs Autonomous Reef Monitoring Structures (ARMS), which are initially seeded on healthy reefs to attract and accumulate a diverse community of marine organisms. Once these structures are biologically enriched, they can be transported to new or artificial reef sites to help initiate and accelerate ecosystem recovery. By introducing ARMS seeded with a healthy mix of coral, invertebrates, and other reef-dwelling species, we aim to promote colonization and enhance biodiversity in developing reefs. This approach not only increases habitat complexity and stability but also supports the transfer of resilient marine communities to areas in need of restoration, promoting long-term ecosystem health and resilience.

The ARMS structures also allow us to scientifically monitor reef health and understand the dynamics of marine biodiversity over time. They are specifically engineered to attract a range of marine micro and macro species, from algae to invertebrates to fish, all of which are crucial for ecosystem balance and food security for surrounding communities. This controlled reintroduction and support of marine life forms not only improves biodiversity, but also creates critical data that helps refine our understanding of reef ecosystems under various environmental pressures, including climate change and human impact.

The project is a collaborative effort with the following key academic partners, each contributing specialized expertise:

Harvard University: Researchers from the Organismic and Evolutionary Biology Department at Harvard lead on biodiversity assessments, focusing on understanding species diversity, ecological interactions, and resilience in marine ecosystems.

Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health: Under the One Health framework, the T.H. Chan School focuses on the intersection of environmental health and community well-being, examining how reef ecosystems impact local health and economic stability. This collaboration emphasizes sustainable practices that benefit both ecosystems and human communities.

University of Toliara: The Institute of Fishery and Marine Science (IHSM) brings extensive local expertise, ensuring that scientific approaches are both contextually relevant and adaptable to Madagascar’s unique marine environment. Additionally, the University of Toliara’s Human Geography Department plays a crucial role in examining the social dimensions of both marine and terrestrial conservation, providing insights into community dynamics, resource use, and socio-economic impacts.

The Beijer Institute of Ecological Economics (Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences): Contributing ecological and economic insights that integrate conservation goals with sustainable resource management models, focusing on balancing ecological integrity with human economic needs.

Institut de Recherche pour le Développement (IRD), France: IRD provides valuable expertise in sustainable fisheries management, contributing research insights that support ecosystem-based approaches to marine resource conservation, with a particular focus on sustaining biodiversity and local livelihoods.

Perry Institute for Marine Science (PIMS): The Perry Institute brings specialized knowledge in coral reef ecology and marine restoration practices, with a focus on developing science-driven solutions to marine conservation challenges. PIMS’s expertise in coral and fish population dynamics supports targeted restoration efforts within the consortium, aligning closely with local and regional conservation objectives.

Through these academic partnerships, we employ rigorous scientific methodology to establish a foundation for long-term ecological monitoring and data-driven resource management.

The Belmont consortium’s approach is deeply rooted in community involvement and cultural relevance. We work closely with local stakeholders to ensure that the artificial reefs meet both ecological and socio-economic needs. Through culturally adapted, user-friendly designs, community members can engage with and even help manage these ARMS systems, fostering a sense of ownership and continuity in marine resource management. This partnership enhances data collection, as community involvement leads to regular, hands-on monitoring and a more sustained conservation effort.

Scientifically, this project offers a replicable model for restoration and marine resource management, especially in areas facing similar environmental and social challenges. By combining rigorous scientific methodology with participatory community engagement, we aim to establish a foundation for long-term ecological monitoring, data-driven resource management, and sustainable economic opportunities. Ultimately, this initiative contributes to global marine science by creating a valuable data set on artificial reef systems while addressing the local imperative of biodiversity conservation and security.

For recent project updates, please visit the ARMSRestore website. You can also find more details of the project in the following recently published paper:

https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/public-health/articles/10.3389/fpubh.2024.1366110/full

By 9am everything was ready and the officials, Monsieur Francois Gilbert, Minister of Fisheries Resources and the Mayor of Belalanda region among them arrived in style together with a national news crew and Emma Gibbons, Director of ReefDoctor. We met their procession just outside the village and the crowd including Ifaty women’s rugby team, the women’s association and a band danced and sang their way to the school where the officials took seats to enjoy some entertainment from local women’s groups from Ifaty (yes these ladies can multi task!), Ambondrolava, Tsivonoe and Mangily. Between groups a band of traditional dancers entertained the crowd. And speeches were given looking forward to the growth of the reef and the future of the Debarcadere.

By 9am everything was ready and the officials, Monsieur Francois Gilbert, Minister of Fisheries Resources and the Mayor of Belalanda region among them arrived in style together with a national news crew and Emma Gibbons, Director of ReefDoctor. We met their procession just outside the village and the crowd including Ifaty women’s rugby team, the women’s association and a band danced and sang their way to the school where the officials took seats to enjoy some entertainment from local women’s groups from Ifaty (yes these ladies can multi task!), Ambondrolava, Tsivonoe and Mangily. Between groups a band of traditional dancers entertained the crowd. And speeches were given looking forward to the growth of the reef and the future of the Debarcadere.

e Ifaty women’s rugby team as they have practiced for a sevens friendly against the women’s team from Tulear. Before I came to Reef Doctor, I was very excited to learn that rugby – especially women’s rugby – had a presence in Madagascar; however, I did not realize what an understatement that is. Rugby is Madagascar’s national sport, and has built a fanatic following among the Malagasy people; even our daily practices regularly drew a crowd from the village. This environment is markedly different than where I learned how to play rugby, in St Andrews, Scotland, where our league games would draw crowds of about 10 people (and we even won the league one year!). However, general enthusiasm, for women’s sports as well as men’s, is only one of the many differences I noticed. On that note, here’s a bit on rugby, Gasy style.

e Ifaty women’s rugby team as they have practiced for a sevens friendly against the women’s team from Tulear. Before I came to Reef Doctor, I was very excited to learn that rugby – especially women’s rugby – had a presence in Madagascar; however, I did not realize what an understatement that is. Rugby is Madagascar’s national sport, and has built a fanatic following among the Malagasy people; even our daily practices regularly drew a crowd from the village. This environment is markedly different than where I learned how to play rugby, in St Andrews, Scotland, where our league games would draw crowds of about 10 people (and we even won the league one year!). However, general enthusiasm, for women’s sports as well as men’s, is only one of the many differences I noticed. On that note, here’s a bit on rugby, Gasy style. The Ifaty team plays on the local football field, which consists of sand, little rocks, bigger rocks, rock substrate underneath a centimeter of sand, and the occasional spike or ten. Practice starts when Coach Elias makes his way to the field, blowing his whistle incessantly throughout the village. The girls come in whatever they own: jean shorts, dresses, skirts, bathing suits, often with necklaces, earrings, and very long nails. Many of the things we take for granted in the West simply aren’t present here: there is a distinct lack of water, first aid, nail clippers, mouth guards, shoes, sports bras, and game kit. During games, the Ifaty team wears the jerseys of the men’s football team; if they want to wear shoes, they must borrow them from another team or go without. However, what they lack in kit, they make up for with determination. As far as how the game

The Ifaty team plays on the local football field, which consists of sand, little rocks, bigger rocks, rock substrate underneath a centimeter of sand, and the occasional spike or ten. Practice starts when Coach Elias makes his way to the field, blowing his whistle incessantly throughout the village. The girls come in whatever they own: jean shorts, dresses, skirts, bathing suits, often with necklaces, earrings, and very long nails. Many of the things we take for granted in the West simply aren’t present here: there is a distinct lack of water, first aid, nail clippers, mouth guards, shoes, sports bras, and game kit. During games, the Ifaty team wears the jerseys of the men’s football team; if they want to wear shoes, they must borrow them from another team or go without. However, what they lack in kit, they make up for with determination. As far as how the game is played, when these girls hit the pitch, it is with no holds barred. There is no such thing as “touch” here; it’s full contact all the time. This tradition is telling of rugby’s history in Madagascar; the game is especially popular in the Tanàna Ambany (low villages) of Antananarivo (Tana), the location of the capital’s poorest inhabitants, as well as the highest rates of illiteracy and idleness. Although rugby in Madagascar is played by the upper class as well, French sociologist Pierre Bourdieu emphasized how especially important the sport is for the lower classes, which lack education and therefore job prospects (source: Razafison, 2010, Africa Review). In fact, many of the country’s rugby stars come from these low villages, and are then catapulted into the national spotlight. In many aspects, Ifaty’s situation is similar to the low villages of Tana, which is why it is so important to make sure the sport is able to thrive here.

is played, when these girls hit the pitch, it is with no holds barred. There is no such thing as “touch” here; it’s full contact all the time. This tradition is telling of rugby’s history in Madagascar; the game is especially popular in the Tanàna Ambany (low villages) of Antananarivo (Tana), the location of the capital’s poorest inhabitants, as well as the highest rates of illiteracy and idleness. Although rugby in Madagascar is played by the upper class as well, French sociologist Pierre Bourdieu emphasized how especially important the sport is for the lower classes, which lack education and therefore job prospects (source: Razafison, 2010, Africa Review). In fact, many of the country’s rugby stars come from these low villages, and are then catapulted into the national spotlight. In many aspects, Ifaty’s situation is similar to the low villages of Tana, which is why it is so important to make sure the sport is able to thrive here. ing session of over 30 primary school teachers in alternative teaching and learning strategies. Approximately 320 girls from all over the Southwest region, including Salary Bay, Desakoa, Ifaty, Satrokala, as well as many girls from primary schools in Tulear, attended the tournament – even a local orphanage brought a team! The girls were split up into groups of 9-10 when they arrived, and all the adults present were given a team to coach throughout the day. (With this experience behind me, I can say that it is not easy to coach a team of Gasy girls with a limited comprehension of the language and no French skills.) The day itself was a blast, and all the girls got to make new friends and encounter different playing styles. In the afternoon, the women’s teams from Ifaty and Tulear played a match before the tournament finals. It was an excellent game, and both teams really left it all on the pitch. Although it was an extremely close game, the final score saw a 10-5 win for Tulear, giving the Ifaty girls all the more reason to practice hard in the coming months as Regionals approach.

ing session of over 30 primary school teachers in alternative teaching and learning strategies. Approximately 320 girls from all over the Southwest region, including Salary Bay, Desakoa, Ifaty, Satrokala, as well as many girls from primary schools in Tulear, attended the tournament – even a local orphanage brought a team! The girls were split up into groups of 9-10 when they arrived, and all the adults present were given a team to coach throughout the day. (With this experience behind me, I can say that it is not easy to coach a team of Gasy girls with a limited comprehension of the language and no French skills.) The day itself was a blast, and all the girls got to make new friends and encounter different playing styles. In the afternoon, the women’s teams from Ifaty and Tulear played a match before the tournament finals. It was an excellent game, and both teams really left it all on the pitch. Although it was an extremely close game, the final score saw a 10-5 win for Tulear, giving the Ifaty girls all the more reason to practice hard in the coming months as Regionals approach.

Women from across the Bay of Ranobe came together in the village of Belalanda on Tuesday 8th March for International Women’s Day and made themselves heard! The usually dusty road to Toliara was alive with colour and music as women’s groups from across the bay, dressed in traditional lamba (sarongs), came together to pray, celebrate, dance and talk.

Women from across the Bay of Ranobe came together in the village of Belalanda on Tuesday 8th March for International Women’s Day and made themselves heard! The usually dusty road to Toliara was alive with colour and music as women’s groups from across the bay, dressed in traditional lamba (sarongs), came together to pray, celebrate, dance and talk. very positive but there is a long way to go before Malagasy women’s rights are recognized in a way that fosters gender equality. Constitutionally, men and women in Madagascar have equal rights but access to employment, services and resources is still limited for the majority of Malagasy women. Madagascar currently ranks 120th out of 128 countries listed on the Women’s Economic Opportunity Index (Economist Intelligence Unit 2012). This pilot index looks at women’s access to economic opportunities worldwide. Prostitution is wide spread in Madagascar and many young women end up working as prostitutes for as little as 2,000 MGA (45p) as there is no viable alternative. Many young girls are sold or rented to older men by their families to make money to buy food.

very positive but there is a long way to go before Malagasy women’s rights are recognized in a way that fosters gender equality. Constitutionally, men and women in Madagascar have equal rights but access to employment, services and resources is still limited for the majority of Malagasy women. Madagascar currently ranks 120th out of 128 countries listed on the Women’s Economic Opportunity Index (Economist Intelligence Unit 2012). This pilot index looks at women’s access to economic opportunities worldwide. Prostitution is wide spread in Madagascar and many young women end up working as prostitutes for as little as 2,000 MGA (45p) as there is no viable alternative. Many young girls are sold or rented to older men by their families to make money to buy food. In rural areas domestic violence against women is common and accepted despite it being against national law. Local law allows wives to be beaten provided her family is compensated. If a woman does something that offends or embarrasses her husband, he is entitled to beat her provided he pays compensation for the beating to her family. This not only allows violence to continue in homes but also makes it acceptable. For these and many other reasons gender equality is essential.

In rural areas domestic violence against women is common and accepted despite it being against national law. Local law allows wives to be beaten provided her family is compensated. If a woman does something that offends or embarrasses her husband, he is entitled to beat her provided he pays compensation for the beating to her family. This not only allows violence to continue in homes but also makes it acceptable. For these and many other reasons gender equality is essential.